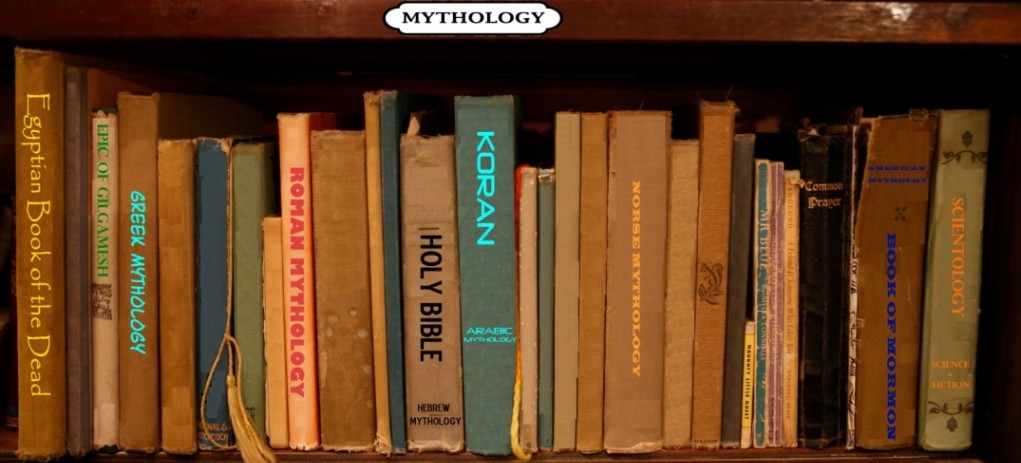

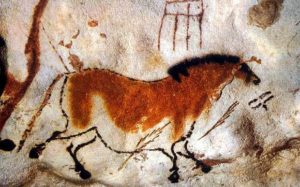

Wounded Bull and Ice Age hunter with atl-atl (spear-thrower).

From nearly 40,000 years ago to almost 10,000 BC, all across southern Europe in over 400 caves and rockshelters, Paleolithic Cave Art blossomed. For the first time in human history, humans depicted…anything.

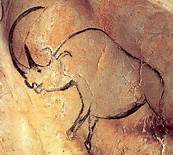

For nearly 30,000, years from Spain to Italy to Eastern Europe this first art, some of it dramatic and skilled, much of it mundane and amateurish (and often difficult to discern just what animal it may be), portrayed mostly the animals in the environment that were important to the Ice Age Hunter’s survival. The vast majority of things depicted were either the animals they hunted and ate (with the occasional edible fish or bird), the dangerous mammals also roaming their environment such as rhinos and lions, or various geometric forms, handprints, and vulvae…lots of vulvae.

No landscapes, no family, no skies, no stars or moon, no fireside scenes, no huts or shelters, no children, no bees or butterflies, no flowers, no edible plants, no tool-making or butchering scenes, no cooking, no shamanistic dancing around the campfire, and no portraits…of any human. If you do see a human depicted at all (very rarely) it is a stick figure, as in the first image above.

The animal is drawn in realistic and frightening detail, a severe gut-shot spear wound with intestines spilling out under pressure: a hunter’s worst nightmare. Not only did the hunter not get a lethal heart-lung kill shot with his spear or dart (thrown with the aid of his atl-atl), but now there’s one big and angry, wounded, animal charging in self-defense, with the hunter lying frozen on the ground in sympathetic nervous system response (often scared shitless, or in this case, showing an autonomic erection). The bird sitting on the weed nearby is an all too common sight around herd animals. Birds feed on the voluminous insects stirred up by grazing mammals. An incredible, indelible realistic scene. I don’t care who you are or what era you lived in, it takes some real balls to hunt large mammals with just a damn spear.

I think it telling that the human is drawn with none of the exquisite detail that is so common in the animals portrayed all over the caves for millennia. This stick figure is characteristic. The very rare humans represented are but undetailed line drawings. One wonders how they viewed themselves as individuals, or how they thought about their mates, offspring, and fellow hunter-gatherers whom were almost never pictured as well.

Some of these Paleolithic illustrators, (not all) were true artists. Incredibly skilled in observation and depiction, they drew and painted detailed images of animal’s muzzles, coats, bodies, and postures in different seasons, in various actions, and rather often in the throes of severe injury from hunters spears and darts, with blood spewing from nose and mouth or defecating from the shock of the sudden wound. These hunters spent hours upon hours, stalking, observing, tracking their prey. They needed intimate knowledge of the animals behavior and appearance. This is what seemed most important to the Paleolithic artists to bother to portray.

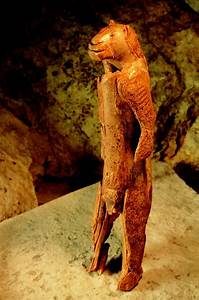

They certainly could have done a portrait of another human, a child, a woman, a hunting partner, in similar lifelike detail, they certainly had the skill…but there’s not one. Just lots of animals, markings, and vulva all over the caves. And when they did depict an entire human beyond a sparse line-drawing sketch of a stick figure, it was an entire female sculpted into a hand-held figurine: “portable art” i.e., carved small images of the female anatomy. Appearing rather late, most of them only after 25,000 BC, they contained only exaggerated breasts and buttocks and vulva, with little to no facial features, or posture, or expression, lacking detail. The “Venus’s” as they are called, number under 150 specimens discovered from all over Ice Age Europe:

All those thousands of animal depictions across hundreds of sites stretching back another to nearly 40,000 BC, and no cave drawings/paintings of females. Only their external genitalia are depicted throughout the caves, and similarly but a few dozen hand-held carved figurines, with exaggerated female body parts and no features, no faces are depicted. It appears that males produced most of the art from this time, depicting what was important, salient to them. Ice Age mammal hunting was the only occupation available to human males at that time and place in human history. It took incredible skill, patience, and incredible bravery. It may have been most on their minds, more than sex, altho female anatomy was a close second.

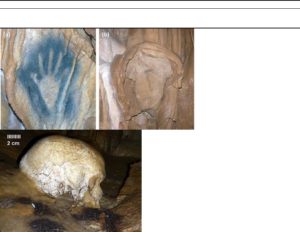

There is an early depiction in a cave of southern France: Vilhonneur, that some claim to be of a human face and is tentatively said to be the “first portrait” ever produced, dating to 27,000 years BC. Here it is to the right of the handprint and above the skull also found in the cave:

There are a few simple lines said to represent a nose and an eye within a natural rock outline. If one can actually discern a face, to me it appears to require more than a bit of imagination, and even if this interpretation were correct, the detail is no more than that found in the Venus figurines above dating to the same Late Paleolithic times.

True portraiture of humans that we are so accustomed to seeing as a given and ubiquitous component of our modern art, where a distinctive individual face is clearly and purposely depicted in detail, easily recognizable as a particular person, and often displaying emotion and/or attitude (think the Mona Lisa) dates at the earliest to the Greco-Roman period of roughly 350BC-350AD. There are also a few earlier stylized depictions of Egyptian and Sumerian kings which do include some individual features, going back to the 2nd and 3rd millennia BC. True portraits of human faces then, of distinct individuals with detailed features and expressions do not appear until tens of thousands of years after the Paleolithic Cave artists portrayed their fine, intimate, lifelike animals.

The question is why not? Why no faces of people, individual persons, with their myriad of expressions and emotions..when many of the Paleolithic artists certainly had the requisite skill to produce such portraiture: Skills they so eloquently displayed in the animals important to them?

My answer is;maybe they didn’t think like us. Maybe they didn’t have the exact same psychology and cultural developments we take for granted as modern humans with over 10,000 years of civilization and cultural advance, habits, and perspectives behind us. Our interpretations of Cave Art over the years has tended to assume they had our cultural practices without question: religion, spirituality, at least shamanism, and our maybe our morals and social interactions of love and family and…you name it. And many of those cultural assumptions just could be wrong. We assume what’s called “behavioral modernity” in Paleolithic humans across all domains of behavior and thought-from just a few scraps of what looks to us as evidence signifying they were “just like us.”

The standard view over the years has been dominated by the early anthropologists and archaeologists, who were religiously, and spiritually inclined such as Abbe Breuil a Catholic priest. It was unlikely for him to interpret the many vulvae depicted in the caves as anything other than hoofprints, a common assumption of many archaeologists long thereafter. Also still common is to interpret the animal paintings, forms, and handprints as having spiritual meaning that would fit the cultural sensibilities of our modern times.

David Lewis William’s very successful book “The Mind in the Cave” leans heavily on a shamanistic interpretation of Paleolithic Art, still in the tradition of interpreting within a magico-religious framework which is so familiar to us in the modern world. Two of the most often cited shaman depictions (though both are a one-off, not at all representative of Cave and Figurine Art) are the lion-man figurine and antlered-man painting:

These are both unique and could be just imaginative art with no special meaning or depiction of shamanistic behavior. Additionally, hunters often wear animals skins and/or a head with antlers to disguise themselves to approach their prey for a closer shot. It is entirely possible that Ice Age hunters took every advantage they could to get as close as possible to their prey, before attempting a spear throw. The stick figure and bird in the first image depicted above have been interpreted spiritually as well instead of being a powerful hunting scene. The bird is said to represent the fallen hunters soul, and the depiction itself just a dream, rather than a very realistic portrayal of an actual hunting disaster.

A more mundane and realistic perspective from an experienced hunter, biologist, and tundra mammal expert, who happens to also be an accomplished artist was provided in the 2006 publication by R. Dale Guthrie:

He personally visited a majority of all of the over 400 caves and rockshelters, and examined scores of artifacts like the figurines. He also has experience with indigenous Alaskan and Canadian Arctic hunters, so he has a perspective on what it is like to stalk, hunt, kill, and butcher large mammals in Ice Age conditions, upon which one depends upon for survival. I think his insights, in place of the usual humanities researcher’s spiritual interpretations is invaluable. He presents a great deal of data from other researchers as well supporting a more realistic and less spiritual view of Paleolithic Art.

One case in point is that recent archaeological studies of cave art settings show no sign of repeated occupation or ritualistic ceremony, shamanistic or otherwise. There is no evidence that crowds of people revisited the cave paintings. Many are also in rather difficult to access recesses in the caves. We might assume they would paint for ritualistic purposes, because ritual is what we would do, or because we would visit paintings as in an art gallery: we would draw and paint for public consumption. Maybe they didn’t. Their motivation cannot be assumed from our modern, standard, cultural practice. There is no evidence for the shamanistic, ritualistic explanations that have been the norm.

In the blurb to Guthrie’s book when it was published over a decade ago, reviewers admitted his extensive analysis, from a hunter’s perspective would upset a lot of people.

Lastly, hunters, both subsistence and modern recreational sports hunters, like their hunting items decorated with hunting scenes. Shotguns are engraved with birds being flushed and shot, or deer in flight, and Eskimo hunters regularly carve hunting scenes onto their weapons. Many of the Paleolithic hunters inscribed their atl-atls and spear shaft straighteners with animals and scenes similar to those found in the caves and rockshelters…detailed animal features, postures, behaviors, and hunting scenes.

I blogged previously and in greater detail on Guthrie’s magnum opus…over 4 years ago HERE.

For an extreme example of a more spiritualistic interpretation of Cave Art, see Graham Hancock’s banned TED talk: Only the introductory remarks directly comment on Cave Art.

Hancock goes beyond Lewis Williams’ shamanistic interpretation and claims that Cave Art was undoubtedly an expression of altered states of consciousness, probably produced by psilocybin mushrooms.

He heads off into psychedelic apologia mostly about DMT visions from the ayahuasca brew, but correctly notes the clinical use of psychedelics to eliminate addictions. He then digresses into a typical spiritual perspective on consciousness including that science can’t really say anything about consciousness as it is altogether too materialistic and reductionist. Hancock claims that we can learn about consciousness only from the ancients and their use of psychedelics… including evidently the shamanistic, psychedelic experiences that produced Cave Art. Hancock’s views represent the complete opposite to Guthrie’s analysis.

Science can say a lot about what the Paleolithic hunters were up to when they painted their animals and it doesn’t take psychedelics to produce the often incomplete and less skilled depictions that are just as common as the marvelous skilled Cave Art that makes it into the coffee table books. The magnificent art doesn’t require psychedelics either, just uncountable hours observing animals, significant artistic talent, and hours of practice, as is so with any accomplished modern artist. The standard magico-religious, spiritualistic lens through which so many have viewed Paleolithic Art has little evidence for it and a lot of yearning behind it.

Religious thinking, as it so often does, clouds our ability to view things head-on.

Paleolithic Art is incredible in its own right. What triggered this explosion of realistic depiction is the subject of another essay and will be explored in my forthcoming book:

“Tools, Concepts, and Consciousness”

For now, it seems Guthrie’s detailed and well-researched tome provides the clearest explanation of the Paleolithic hunters first foray into full human expression without a spiritual or psychedelic agenda behind it.

(303)